“Power is not a means; it is an end…The object of power is power.” –Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell.

My novel Graëlstorm delves into the timeless tug-of-war between liberty and power. In this fictional cosmos, three immortal beings called Arkheïa reign over the mortal realm using a genetically engineered race of Graëlheem to impose their will. The Chosen are an elite military force of Graëlheem bound by vows of loyalty, celibacy, and obedience to the Arkheïa. But when one of their clans is unjustly expelled from the Chosen, resistance brews within their ranks, sparking a confrontation between them, the Arkheïa, and the other Graëlheem factions.

Here’s a snippet of dialogue from a scene where the Arkheïa debate their response to the dissident clan’s disobedience:

Angelo: “We were given dominion over the Cosmos. Our will is absolute – there is no authority higher than us!”

Luther: “When have I said our authority is debatable?”

Angelo: “We have [the Chosen’s] covenants. Obedience is demanded, not granted at their favour.”

Luther: “…covenants do not win their hearts and minds.”

Celestine: “The Chosen would never rise against us. They would not dare!”

Luther: “They don’t have to…all they have to do is cease to cooperate. Nothing weakens authority more than resistance.”

Angelo: “…we dictate; we do not negotiate!”

Luther: …and if they refuse to bow down?”

Angelo: “Then we snap their backs!”

Chiefs, Thrones and Beyond

Since people first banded together for protection and support, they’ve looked to a leader for organization and order. We’ve seen how modern society becomes anarchy without a government in place—law and order break down, warlords or gangs fill the void, and daily life for most becomes a battle to survive. That said, a regime with too much power can result in oppression and the loss of our freedoms. A fair society depends on a balance between authority and rights.

The oldest form of government is autocracy, which concentrates power in an individual or party. Over time, it evolved from family patriarchs to tribal chiefs, monarchs, and dictators. While democracy existed in ancient Greece and Rome, it was a VIP club only the elite could join. It wasn’t until the late 18th and 19th centuries that more people gained a voice, a trend that gathered steam in the 20th century thanks to wider emancipation and decolonization. Despite this, much of the world is under autocratic rule. To understand why, we need to look through the eyes of Enlightenment thinkers who still shape our views.

Necessary Evil?

Before the 1600s, kings and queens ruled vast swaths of the world. They often claimed to be anointed by God, which sanctified the monarchy and made themselves untouchable. Even though he rejected the idea of divine right to rule, philosopher John Hobbes was the ultimate believer in this kind of absolute autocracy—strong leadership with everyone in line. He thought it was essential to tame the selfish and violent side of human nature he had witnessed during the English Civil War. This conflict tore the country into political and sectarian factions. Communities turned on each other, families were ripped apart, and the death toll reached nearly five percent of the population. Hobbesian autocracy is how modern dictators rule the roost: no debate or check on their power. They call the shots, and no one can question them.

Hobbes’s contemporary, John Locke, saw power and immunity as a toxic mix. He agreed with strong government, but he rejected the idea of an all-powerful leader accountable to no one. That would be a fast track to tyranny. Instead, he argued that everyone is born with certain inalienable rights, such as life, liberty, and property, and it is the government’s job to protect them. Should it fail to do this, the people have the right to overthrow it. Charles Montesquieu agreed with Locke, but he went a step further. His key contribution was about the separation of powers and checks and balances—splitting a government’s functions into independent branches and making sure they all kept each other in line. That’s basically the American political system, inspired by Locke and Montesquieu’s ideas.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau took it to another level. He believed in people power, where citizens themselves make decisions rather than concentrating authority in a central government. This is how modern Swiss democracy works—citizens have a voice in all important decisions through referendums of the entire electorate. Elections are decided by proportional representation, and local and regional governments handle significant decision-making. Even the presidency is largely ceremonial, rotating annually among a federal council comprising seven members from different political parties who make decisions collectively.

Autocracy Unmasked

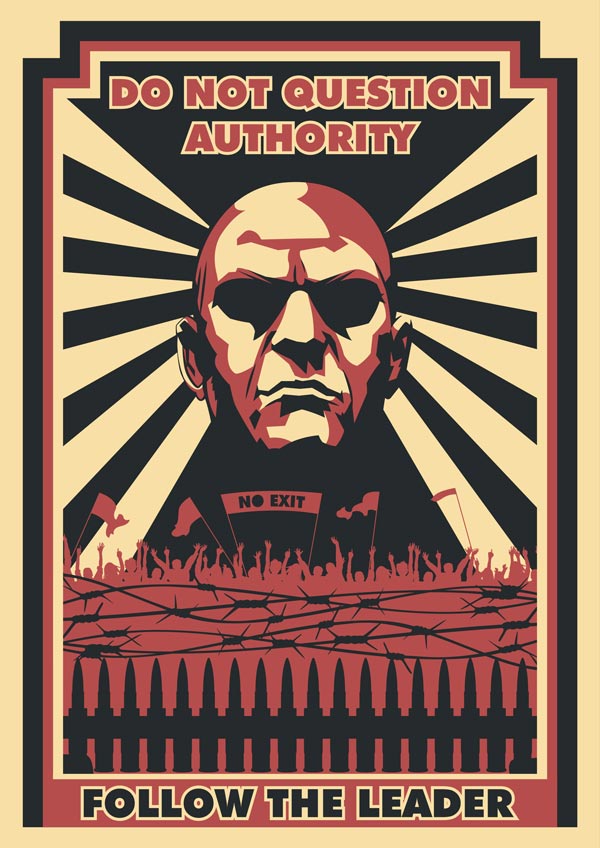

Autocracies come in all shapes and sizes, from those tied to religion to those driven by left- or right-wing ideas. They can be run by civilians or the military and can be led by an individual or a single party. While some bring economic growth, others plunge their people into destitution through corruption and mismanagement. Some even pretend to be democracies, but they rig elections or limit choices to keep their grip on power. If left unchecked, they can become totalitarian regimes—control freaks dictating everything from your beliefs and education to what media you consume, and even your reproductive choices. But all these Hobbesian autocracies have one thing in common: power matters more than people.

Recent trends show autocracies are on the rise and gaining momentum. So, what makes people rally behind authoritarian figures? When people feel sidelined by society or uncertain about their finances, they often gravitate towards charismatic leaders—self-styled “strongmen” who promise them easy fixes. Unlike dictators of the past who seized power through force, modern autocrats use manipulation, deceit, and gaslighting to sway followers and suppress dissent. Warning signs of budding autocrats include tactics like sowing division, undermining democratic norms, spreading misinformation, fuelling hatred towards scapegoats, bullying critics, and demonizing opponents—all under the guise of strengthening the nation under one leader, one goal. And watch out for leaders extending their term limits. What might seem innocuous can morph into a permanent fixture, such as “president for life.” History warns us that leaders who try to hang on to power rarely have the people’s welfare at the top of their agenda.

Democracies aren’t perfect either. Politicians can make short-term decisions just to score points with voters, or parties get so entrenched in their views that nothing gets done because they can’t agree on anything. And then there’s the winner-takes-all system, where just over half the country gets to impose their will, leaving nearly half the country steamrolled into something they didn’t want. But on the flip side, real democracies come with checks and balances, terms limits, elections for change, peaceful transitions of power, and protection of people’s rights. As Winston Churchill observed, democracy isn’t perfect, but it’s better than any other systems we’ve attempted.

Dystopia

Iconic works such as Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Huxley’s Brave New World, DC Comics’ V for Vendetta, Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and Collins’s The Hunger Games all portray oppressive regimes that maintain power through tactics like coercion, surveillance, and manipulation of the truth. These stories are not just entertainment; they are warnings. And like fairy talesthey are dark for a reason—they shake us awake and alert us to danger. The underlying message of Little Red Riding Hood isn’t really about wolves: it’s a reminder that there are people out there who may trick or harm us. Dystopian stories are the same, pushing us to ask, if you ignore the warnings, where does it end?

Humans will always struggle between the need to be led and the desire to be free, creating an endless tug-of-war between liberty and power. Dystopia makes these abstract ideas more relatable by playing out dramas for us to witness first-hand. By exaggerating scenarios and adding tension, they grab our attention and stir our emotions; they give us a cause to root for. This drives their point home better than any speech or essay—not just about the consequences of unchecked power, but also the resilience of the human spirit to resist and overcome it. As author Ally Condie observed, “The beauty of dystopia is that it lets us vicariously experience future worlds while we still have the power to change our own.”